Vivek Kumar Jha is a PhD student in extragalactic astronomy at the Aryabhatta Research Institute of Observational Sciences (ARIES) in Nainital, Uttarakhand, India.

This post is part of a series on how the COVID-19 pandemic is affecting the personal and professional lives of physicists around the world. If you’d like to share your own perspective, please contact us at pwld@ioppublishing.org.

My research work involves continuously monitoring active galactic nuclei (AGN) in the optical wavelength range through different telescopes. I spend most of my time at ARIES, and the remainder of my time at the institute’s observatory in Devasthal, which is located 70 km further into the Himalayas. Some of our observations are also done remotely with robotic telescopes in other parts of the world and with space-based telescopes.

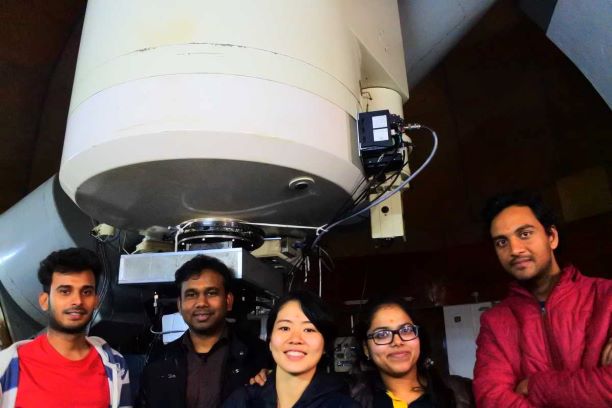

My work is broadly divided into two parts: performing observations for a few nights every month at Devasthal, and reducing, analysing and modelling data obtained from this and other telescopes to get scientific outputs. On nights when we are scheduled to observe, we have to be present at the observatory along with the technical staff stationed there to help us run everything smoothly. When not observing, we work in our institute’s office cubicles. Most often our working hours extend into the night, with occasional tea and coffee breaks. In terms of group activities, we have daily discussions over arXiv papers within our research groups, weekly discussions with other research fellows in our science club and occasional seminars during the afternoon. We have some sports activities and we usually play volleyball, badminton and table-tennis during the evening.

The world’s biggest lockdown

Owing to safety concerns, ARIES asked us to leave a few days before 25 March, when India’s central government began to enforce the world’s biggest lockdown – effectively confining 1.3 billion people to their homes. Now, there are only a few essential staff on duty at the institute and the observatory. The technical operators at the observatory have been remarkable, keeping the telescope up and running even in these difficult times. Meanwhile, I returned to my home in New Delhi and am currently working from there.

Working remotely is a familiar thing for people involved in astronomy. Whether it’s using data from the robotic telescopes, filing online observation requests or holding meetings with our collaborators over Skype, we regularly work remotely even in normal times. And of course, for space-based telescopes, working remotely is the only possibility we have! With that in mind, I expected my experience of this pandemic to be more of a “change-of-workplace” rather than “work-coming-to-a-halt”. Working from home didn’t seem challenging at first sight, especially for those of us already equipped with the essentials – namely a computer, notepads and a good Internet connection.

But what I have discovered is that it is very difficult to work as usual from home. I read somewhere that the experience is like inviting your family to the workplace during office hours. Even the act of getting up and then walking a few feet to your desk doesn’t feel encouraging most of the time. The atmosphere doesn’t help either, with everyone anxious about what happens next. There are rumours galore even in the national capital – sometimes about food shortages leading to panic buying, sometimes about free buses for migrants leading to some crazily large gatherings of people trying to get home.

Having said that, in these uncertain times it’s better to cherish what we have and not fall into the trap of negativity. I plan my day in the morning and make a list of things to do. My usual workday now involves reading relevant papers, working on my current project for a few hours, learning techniques online to solve some problems, and talking over the phone with friends. This pandemic has given us a good opportunity to catch up with old friends and family members, which eventually reduces the isolation we feel. But of course, working in a group, surrounded by like-minded people who share the same feelings as we go through the little ups and downs of research life – this is a component that suddenly disappeared. We try to make up for that by scheduling video calls occasionally, but the feeling of sitting together and having a chat can’t be replaced at all. Meeting face-to-face is a luxury we can’t afford right now.

Adjusting to a new normal

Initially, India’s national lockdown was supposed to end on 14 April, but after looking at the global and national trends, the government has extended it for another few weeks, to 3 May. I have prepared myself accordingly. Our group meetings have shifted to video conference apps like Skype or Zoom. Analysis work for the data I already have continues with occasional inputs from my supervisor. I plan to get a draft ready by the end of this month. On the observational front, I am able to submit observation requests for the robotic telescopes online, while at the Devasthal observatory my observations are performed by the technical operators with a request over a phone call. So far it has worked out, and I am hopeful it will continue this way until the crisis subsides.

Because we miss the company of friends and colleagues at ARIES, we decided to meet twice a week over Skype for an hour. The director of our institute has initiated a seminar series over Zoom that has been highly successful, with more than 40 people participating every day. I have also signed up to present a talk on this platform. Even though we miss being with our community, we can at least connect with people if we want to, thanks to modern technology. No-one can imagine what our life would have been like had the disease struck in the pre-Internet era.

Even though this crisis has reduced my usual work hours, my ability to work and communicate has not been lost. Luckily, my research doesn’t involve a lab that has been shut; although it involves a few telescopes, these have been functioning so far, albeit with reduced technical staff. The most difficult question I face these days is from my mother. Every morning while having tea, she has been asking, “When will this situation improve?” I have not been able to answer the question convincingly and hence it persists.

Physics in the pandemic: ‘I hope the rest of the world can see hope from my experience’

Predictions and hopes

Deep down, no-one among us has a convincing answer, as this is a crisis we have never experienced. It may extend for months, and at the moment there is no end in sight. Even if the virus goes away, the effects it will leave behind will be profound. Almost all the national and international conferences have been cancelled, including some as far off as November, which hampers our opportunities to interact with the research community. In the near future, work on ground as well as space-based telescopes will definitely slow down, and some projects may not even get started.

One final note. We have been divided along the lines of religion, race, caste and gender for a very long time. But for the time being, the talk of division along these lines has been replaced by talk of doctors, equipment and medical research. If we are seeking a positive message to come out of this crisis, I think it is that we should be united from now on, however Utopian it may sound. Leaders have been talking about the world being different after this crisis is over. I hope one aspect of this difference is that we can rise above the petty divisions among us and bring togetherness to all of humanity.