A European mission that will take the closest-ever pictures of the Sun and give scientists their first look at the star’s uncharted poles is preparing to launch. The craft, called the Solar Orbiter, is part of a group of missions and telescopes that are fostering a new era of solar research.

“Nobody has been able to take images this close to the Sun before,” says Helen O’Brien at Imperial College London, who manages the magnetometer instrument on the European Space Agency (ESA) Solar Orbiter, which also has NASA involvement. “We should see some beautiful images.”

On 9 February, the €500-million (US$550-million) Solar Orbiter spacecraft will launch from Cape Canaveral in Florida. Equipped with ten instruments, it will journey to Mercury’s orbit in the first stage of a mission that could last ten years.

Its main aim is to investigate interactions between the Sun and its heliosphere — the bubble of the Sun’s activity in space, says O’Brien. “It’s really important to work out how the energy propagates from the surface out into interplanetary space.”

Up close and personal

The spacecraft will be placed into an orbit that will bring it, at its closest, just 42 million kilometres, or 0.28 astronomical units, from the Sun (1 au is the distance between Earth and the Sun). It will take about two years to reach this orbit using gravitational assists from Venus.

Scientists also hope to use the Solar Orbiter to work out what drives the solar wind — the stream of particles and plasma that leaves the Sun’s outer atmosphere, called the corona, at hundreds of kilometres per second. Because of its proximity to the Sun, the craft will be able to take pristine measurements of the solar wind and energetic particles before they have been modified by their journey through space.

The Solar Orbiter’s main science phase will begin in November 2021 and last for four years. But if the mission is extended, as ESA scientists hope it will be, the craft would enter a second phase, which would allow it to image the Sun’s poles for the first time. Over several years, mission controllers would raise the angle of the spacecraft’s orbit above the plane of the planets, using the gravitational pull of Venus. Reaching a maximum inclination of 33 degrees above the planetary plane, this will enable the craft to go up and over the Sun.

“We will gradually fly out of the ecliptic plane, and that will give us the first-ever views of the solar poles,” says Daniel Müller, a solar physicist at ESA’s European Space Research and Technology Centre in Noordwijk, the Netherlands, who is the project scientist on the mission. “We believe that is key to better understanding the Sun’s magnetic activity cycle, because over a timescale of 11 years, the magnetic polarity of the Sun changes, and the north pole becomes the south pole.” A previous mission, ESA and NASA’s Ulysses spacecraft, flew over the poles in the 1990s and 2000s — but it had no cameras.

Most of the orbiter’s solar-powered instruments are behind a 40-centimetre-thick titanium shield. Although the front of this heat shield will bear the brunt of the 500 °C heat, the shielding and the effects of the vacuum of space mean that the instruments directly behind it will remain below 50 °C.

These instruments include several cameras, which will peer through small holes in the heat shield to take images of the Sun from closer than any spacecraft in history. Protruding from the back of the spacecraft is a 4.4-metre-long boom carrying instruments such as the magnetometer, which will measure the solar wind’s magnetic field.

Tag team

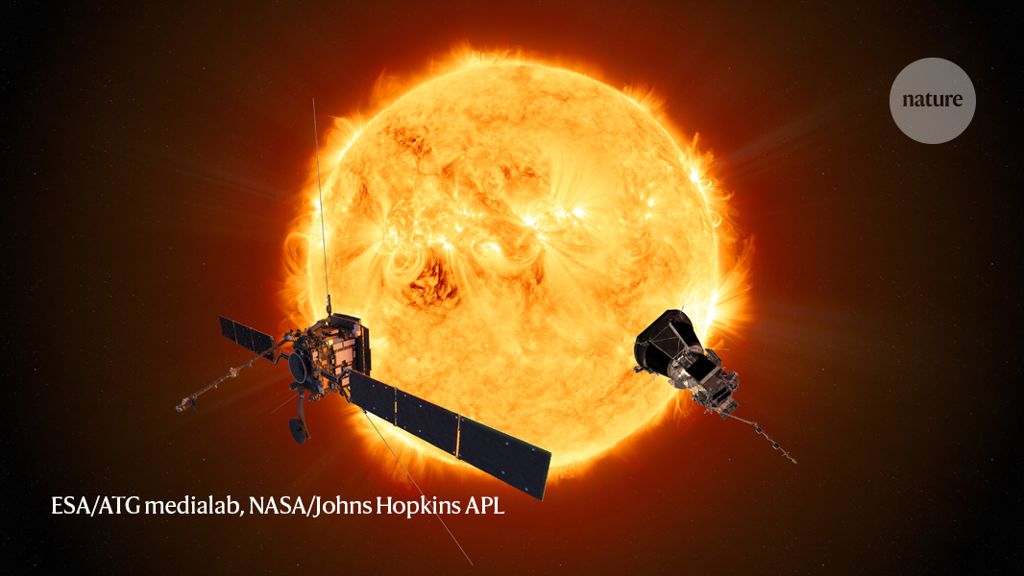

The Solar Orbiter is heading to the Sun after NASA’s Parker Solar Probe, which launched in August 2018. That craft is making the closest-ever approach to the Sun — just 0.04 au — but does not have cameras to image the star directly.

“The two missions are going out for the same science, but really going after it with different methods,” says Nicola Fox, director of heliophysics at NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington DC. “There will definitely be campaigns where Solar Orbiter will have all of its instruments switched on and Parker Solar Probe will be in very close. We’ll be able to do some very cool collaborative science.”

Together, the spacecraft — along with the Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope in Hawaii, which released its first images last month — will be part of an “unprecedented” period in our understanding of the Sun, says Nour Raouafi, the project scientist for the Parker Solar Probe, who is based at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland. “The next decade will be the golden age of solar and heliophysics research.”