This story was produced by Grist and co-published with Fresnoland.

The land of the Central Valley works hard. Here in the heart of California, in the most productive farming region in the United States, scrutinizingly every square inch of land has been razed, planted, and shaped to support large-scale agriculture. The valley produces almonds, walnuts, pistachios, olives, cherries, beans, eggs, milk, beef, melons, pumpkins, sweet potatoes, tomatoes, and garlic.

This economic mandate is well-spoken to the naked eye: Trucks laden with fertilizer or diesel trundle lanugo arrow-straight roads past square field without square field, each one dumbo with tomato shrubs or nut trees. Canals slice between orchards and acres of silage, pushing nuts-and-bolts irrigation water through a network of laterals from sublet to farm. Cows jostle for space underneath metal awnings on crowded patches of dirt, emitting a stench that wafts over nearby towns.

There is one exception to this law of productivity. In the midst of the valley, at the confluence of two rivers that have been dammed and diverted scrutinizingly to the point of disappearance, there is a wilderness. The ground is covered in water that seeps slowly wideness what used to be walnut orchards, the surface buzzing with mosquitoes and songbirds. Trees climb over each other whilom thick knots of reedy grass, consuming what used to be levees and culverts. Beavers, quail, and deer, which haven’t been seen in the zone in decades, tiptoe through swampy ponds early in the morning, while migratory birds toboggan overnight on knolls surpassing flying south.

Austin Stevenot, who is in tuition of maintaining this restored jungle of water and wild vegetation, says this is how the Central Valley is supposed to look. Indeed, it’s how the land did squint for thousands of years until white settlers arrived in the 19th century and remade it for industrial-scale agriculture. In the era surpassing colonization, Stevenot’s siblings in the California Miwok tribe used the region’s native plants for cooking, basket weaving, and making herbal medicines. Now those plants have returned.

“I could walk virtually this landscape and go, ‘I can use that, I can use this to do that, I can eat that, I can eat that, I can do this with that,’” he told me as we crush through the flooded land in his pickup truck. “I have a variegated way of looking at the ground.”

You wouldn’t know it without Stevenot there to point out the signs, but this untamed floodplain used to be a workhorse parcel, just like the land virtually it. The fertile site at the confluence of the San Joaquin and Tuolumne rivers once hosted a dairy operation and a cluster of yield fields owned by one of the county’s most prominent farmers. Virtually a decade ago, a conservation nonprofit worked out a deal to buy the 2,100-acre tract from the farmer, rip up the fields, and restore the warmed-over vegetation that once existed there. The conservationists’ goal with this $40 million project was not just to restore a natural habitat, but moreover to pilot a solution to the massive water management slipperiness that has seized California and the West for decades.

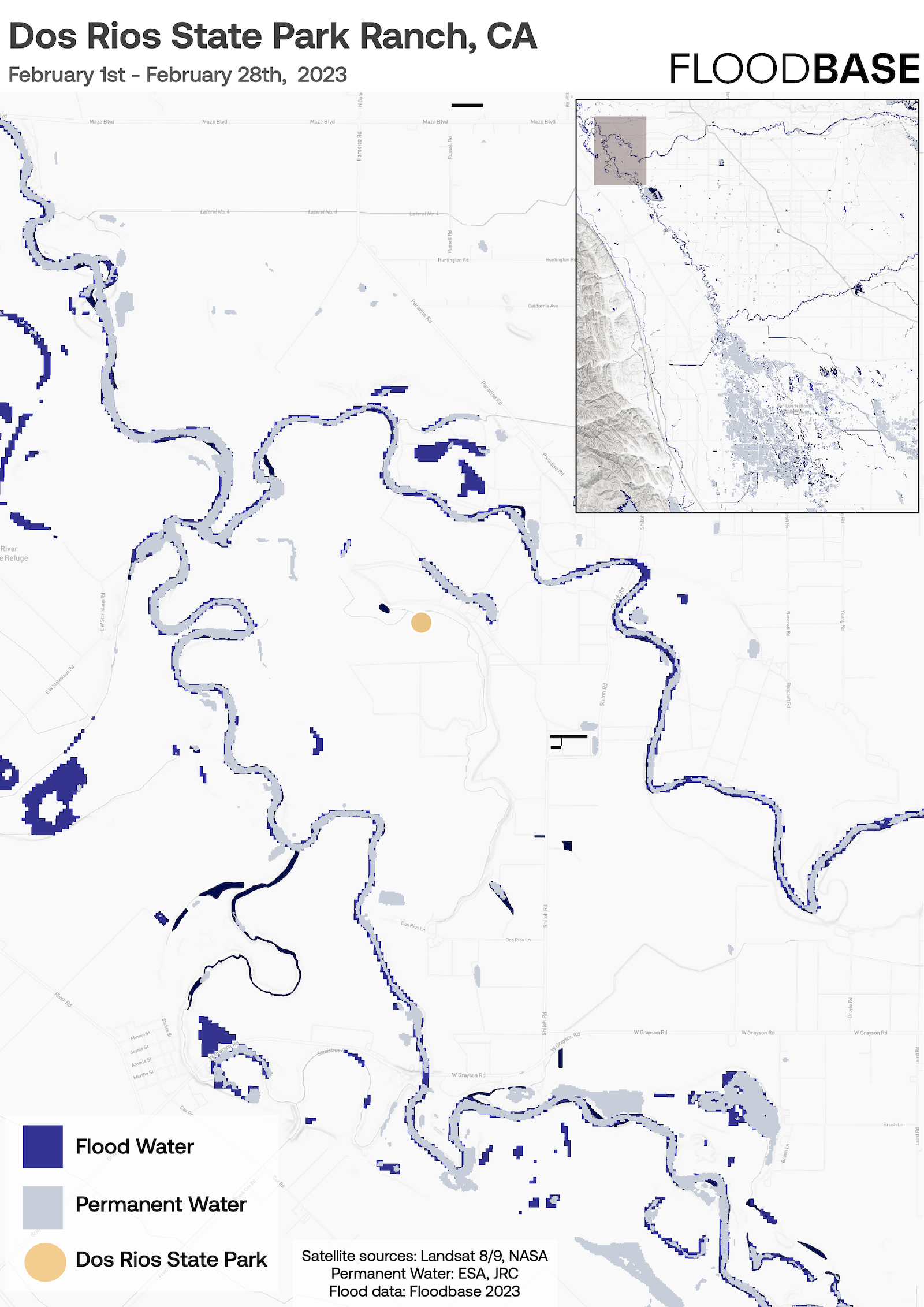

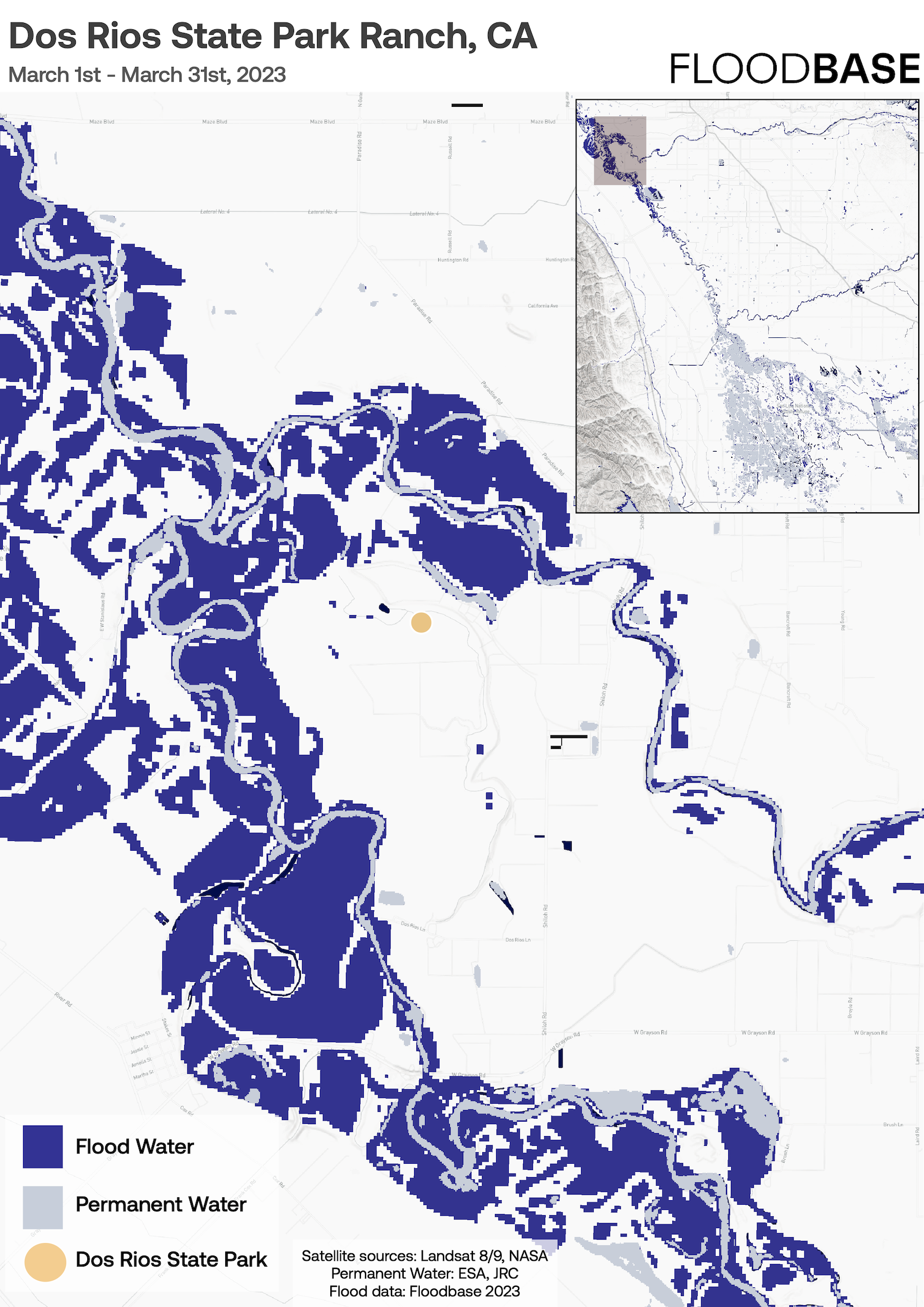

Like many other parts of the West, the Central Valley unchangingly seems to have either too little water or too much. During dry years, when mountain reservoirs dry up, farmers mine groundwater from aquifers, draining them so fast that the land virtually them starts to sink. During wet years, when the reservoirs fill up, water comes streaming lanugo rivers and bursts through white-haired levees, flooding farmland and inundating valley towns.

The restored floodplain solves both problems at once. During wet years like this one, it absorbs glut water from the San Joaquin River, slowing lanugo the waterway surpassing it can rush downstream toward large cities like Stockton. As the water moves through the site, it seeps into the ground, recharging groundwater aquifers that farmers and dairy owners have tuckered over the past century. In wing to these two functions, the restored swamp moreover sequesters an value of stat dioxide equivalent to that produced by thousands of gas-powered vehicles. It moreover provides a oasis for migratory birds and other species that have faced the threat of extinction.

“It’s been wondrous just getting to see nature take it when over,” Stevenot said. “When you go out to a commercially farmed orchard or field, and you stand there and listen, it’s sterile. You don’t hear anything. But you come out here on that same day, you hear insects, songbirds. It’s that lower part of the ecosystem starting up.”

Water flows through part of Dos Rios Ranch Preserve. The former farmland now acts as a storage zone for floodwaters during wet years. Cameron Nielsen / Grist

Austin Stevenot walks through Dos Rios Ranch Preserve. Stevenot manages the restored floodplain site. Cameron Nielsen / Grist. The floodplain, which is off limits for hunting, fishing, or dumping, absorbs glut water from the San Joaquin and Tuolumne Rivers. Rich Pedroncelli / AP Photo

Stevenot’s own career path mirrors that of the land he now tends. Surpassing he worked for River Partners, the small conservation nonprofit that ripened the site, he spent eight years working at a packing plant that processed cherries and onions for export wideness the country. He was a lifelong resident of the San Joaquin Valley, but had never been worldly-wise to use the traditions he’d learned from his Miwok family until he started working routine maintenance at the floodplain project. Now he presides over the whole ecosystem.

This year, without a waterflood of winter rain and snow, water rolled lanugo the San Joaquin and Tuolumne rivers, filling up the site for the first time since it had been restored. As Stevenot guided me wideness the landscape, he showed me all the ways that land and water were working together. In one area, water had spread like a sheet wideness three former fields, erasing the divisions that had once separated acres on the property. Elsewhere, birds had scattered seeds throughout what was once an orderly orchard, so that new trees soon obscured the old furrows.

The outstart of the restoration project, known as Dos Rios, has worked wonders for this small section of the San Joaquin Valley, putting an end to frequent flooding in the zone and interchange long-held attitudes well-nigh environmental conservation. Plane so, it represents just a chink in the armor of the Central Valley, where agricultural interests still tenancy scrutinizingly all the land and water. As climate transpiration makes California’s weather whiplash increasingly extreme, creating a trundling of drought and flooding, inflowing experts say replicating this work has wilt increasingly urgent than ever.

But towers flipside Dos Rios isn’t just well-nigh finding money to buy and reforest thousands of acres of land. To create a network of restored floodplains will moreover require reaching an wind-down with a powerful industry that has historically clashed with environmentalists — and that produces fruit and nuts for much of the country. Making good on the promise of Dos Rios will midpoint inveigling the state’s farmers to occupy less land, gargle with less water, and produce less food.

Cannon Michael, a sixth-generation farmer who runs Bowles Farming Visitor in the heart of the San Joaquin Valley, says such a shift is possible, but it won’t be easy.

“There’s a limited resource, there’s a warming climate, there’s a lot of constraints, and a lot of people are white-haired out, not unchangingly coming when to the farm,” Michael said. “There’s a lot of transition that’s happening anyway, and I think people are starting to understand that life is gonna change. And I think those of us who want to still be virtually the valley want to icon out how to make the outcome something we can live with.”

You can think of the last century of environmental manipulation in the Central Valley as one long struggle to create stability. Alfalfa fields and citrus orchards guzzle a lot of water, and nut trees have to be watered unceasingly for years to reach maturity, so farmers seeking to grow these crops can’t just rely on water to fall from the sky.

In the early 19th century, as white settlers first personal land in the Central Valley, they found a turbulent ecosystem. The valley functioned as a phlebotomize for the mountains of the Sierra Nevada, sluicing trillions of gallons of water out to the ocean every spring. During the worst inflowing years, the valley would turn into what one 19th-century observer called an “inland sea.” It took a while, but the federal government and the powerful farmers who took over the valley got this water under control. They built dozens of dams in the Sierra Nevada, permitting them to store melting snow until they wanted to use it for irrigation, as well as hundreds of miles of levees that stopped rivers from flooding.

But by restricting the spritz of the valley’s rivers, the government and the farmers moreover desiccated much of the valley’s land, depriving it of floodwaters that had nourished it for centuries.

“In the old days, all that floodwater would spread out over the riverbanks into proximal areas and sit there for weeks,” said Helen Dahlke, a hydrologist at the University of California, Davis, who studies floodplain management. “That’s what fed the sediment, and how we replenish our groundwater reserves. The floodwater really needs to go on land, and the problem is that now the land is mainly used for other purposes.”

The minutiae of the valley moreover unliable for the prosperity of families like that of Bill Lyons, the rancher who used to own the land that became Dos Rios. Lyons is a third-generation family farmer, the heir to a farming dynasty that began when his great-uncle E.T. Mape came over from Ireland. With his shock of gray hair and his standard uniform of starched dress shirt and jeans, Lyons is the image of the modern California farmer, and indeed he once served as the state’s secretary of agriculture.

Lyons has expanded his family’s farming operation over the past several decades, stretching his nut orchards and dairy farms out wideness thousands of acres on the west side of the valley. But his territory straddles the San Joaquin River, and there was one sublet property that unchangingly seemed to go underwater during wet years.

“It was an extremely productive ranch, and that was one of the reasons it attracted us,” said Lyons. But while the land’s low-elevation river frontage made its soil fertile, that same geography put its harvests at risk of flooding. “Over the 20 years that we owned it, I believe we got flooded out two or three times,” Lyons added.

In 2006, as he was repairing the sublet without a flood, Lyons met a biologist named Julie Rentner, who had just joined River Partners. The conservation nonprofit’s mission was to restore natural ecosystems in river valleys wideness California, and it had completed a few unobtrusive projects over the previous decade, most of them on small chunks of not-too-valuable land in the north of the state. As Rentner examined the overdeveloped land of the San Joaquin Valley, she came to the conclusion that it was ready for a much larger restoration project than River Partners had overly attempted. And she thought Lyons’ land was the perfect place to start.

Most farmers would have bristled at such a proposition, expressly those with deep roots in a region that depends on agriculture. But unlike many of his peers, Lyons once had some wits with conservation work: He had partnered with the U.S. Forest Service in the 1990s on a project that set whispered some land for the Aleutian goose, an endangered species that just so happened to love roosting on his property. As Lyons started talking with Rentner, he found her practical and detail-oriented. Within a year, he and his family had made a handshake deal to sell her the flood-prone land. If she could find the money to buy the land and turn it into a floodplain, it was hers.

For Rentner, the process wasn’t anywhere near so easy. Finding the $26 million she needed to buy the land from Lyons — and the spare $14 million she needed to restore it — required scraping together money from a rogues’ gallery of funders including three federal agencies, three state agencies, a local utility commission, a nonprofit foundation, the electric utility Pacific Gas & Electric, and the beer visitor New Belgium Brewing.

“I remember taking so many tours out there,” said Rentner, “and all the public funding organ partners would go, ‘OK, so you have a million dollars in hand, and you still need how many? How are you going to get there?’”

“I don’t know,” Rentner told them in response. “We’re just gonna alimony writing proposals, I guess.”

Even once River Partners bought the land in 2012, Rentner found herself in a permitting nightmare: Each grant came with a separate set of conditions for what River Partners could and couldn’t do with the money, the deed to Lyons’ tract came with its own restrictions, and the government required the project to undergo several environmental reviews to ensure it wouldn’t harm sensitive species or other land. River Partners moreover had to hold dozens of listening sessions and polity meetings to quell the fears and skepticism of nearby farmers and residents who worried well-nigh shutting lanugo a sublet to inflowing it on purpose.

It took increasingly than a decade for River Partners to well-constructed the project, but now that it’s done, it’s well-spoken that all those fears were unfounded. The restored floodplain undivided a waterflood from the huge “atmospheric river” storms that drenched California last winter, trapping all the glut water without flooding any private land. The removal of a few thousand acres of farmland hasn’t put anyone out of work in nearby towns, nor has it hurt local government budgets. Indeed, the groundwater recharge from the project may soon help restore the unhealthy aquifers unelevated nearby Grayson, where a community of virtually 1,300 Latino agricultural workers has long avoided drinking well water contaminated with nitrates.

As new plants take root, the floodplain has wilt a self-sustaining ecosystem: It will survive and regenerate plane through future droughts, with a full hierarchy of pollinators and wiring flora and predators like bobcats. Except for Stevenot’s routine wind-up and road repair, River Partners doesn’t have to do anything to alimony it working in perpetuity. Come next year, the organization will hand the site over to the state, which will alimony it unshut as California’s first new state park in increasingly than a decade and let visitors wander on new trails.

“After three years of intensive cultivation, we walk away,” said Rentner. “We literally stopped doing any restoration work. The vegetation figures itself out, and what we’ve seen is, it’s resilient. You get a big deep inflowing like we have this year, and without the floodwaters recede what comes when is the native stuff.”

Dos Rios has managed to transpiration the monitoring of one small corner of the Central Valley, but the region’s water problems are gargantuan in scale. A recent NASA study found that water users in the valley are over-tapping aquifers by well-nigh 7 million acre-feet every year, sucking half a Colorado River’s worth of water out of the ground without putting any back. This overdraft has created zones of lattermost land subsidence all over the valley, causing highways to one-liner and buildings to sink dozens of feet into the ground.

At the same time, floods are moreover getting harder to manage. The “atmospheric river” storms that drench California every few years are rhadamanthine increasingly intense as the earth warms, pushing increasingly water through the valley’s twisting rivers. The region escaped a catastrophic inflowing this year only thanks to a slow spring melt, but the future risks were clear. Two levees splash in the eastern valley town of Wilton, withal the Cosumnes River, killing three people, and the historically Black town of Allensworth flooded as the once-dry Tulare Lake reappeared for the first time since 1997.

Fixing the state’s distorted water system for an era of climate transpiration will be the work of many decades. In order to comply with California’s landmark law for regulating groundwater, which will take full effect by 2040, farmers will have to retire as much as a million acres of productive farmland, wiping out billions of dollars of revenue. Protecting the region’s cities from flooding, meanwhile, will require spending billions increasingly dollars to perpetuate white-haired dirt levees and channels.

In theory, this dual mandate would make floodplain restoration an platonic way to deal with the state’s water problems. But the scale of the need is enormous, equivalent to dozens of projects on the same scale as Dos Rios.

“Dos Rios is good, but we need 50 increasingly of it,” said Jane Dolan, the chair of the Central Valley Inflowing Protection Board, a state organ that regulates inflowing tenancy in the region. “Do I think that will happen in my lifetime? No, but we have to alimony working toward it.” Fifty increasingly projects of the same size as Dos Rios would span increasingly than 150 square miles, an zone larger than the municipality of Detroit, Michigan. It would forfeit billions of dollars to purchase that much valuable farmland, saw yonder old levees, and plant new vegetation.

As successful as Rentner was in finding the money for Dos Rios, the nonprofit’s piecemeal tideway could never fund restoration work at this scale. The only viable sources for that much funding are the state and federal governments. Neither has overly devoted significant public dollars to floodplain restoration, in large part considering farmers in the Central Valley haven’t supported it. But that has started to change. Older this year, state lawmakers set whispered $40 million to fund new restoration projects. Governor Gavin Newsom, fearing a upkeep crunch, tried to slash the funding at the start of the year, but reinserted it without furious protests from local officials withal the San Joaquin. Most of this new money went straight to River Partners, and the organization has once started to well-spoken the land on a site next to Dos Rios. It’s moreover in the process of latter on flipside 500-acre site nearby.

But plane if nonprofits like River Partners get billions increasingly dollars to buy agricultural land, creating the ribbon of natural floodplains that Dolan describes will still be difficult. That’s considering river land in the Central Valley is moreover some of the most productive agricultural land in the world, and the people who own it have no incentive to forgo future profits by selling.

“Maybe we could do it some time lanugo the road, but we’re farming in a pretty water-secure area,” said Cannon Michael, the sixth-generation farmer from Bowles Sublet whose land sits on the upper San Joaquin River. The aquifers underneath his property are substantial, fed by seepage from the river, and he moreover has the rights to use water from the state’s waterway system. “It’s a nonflexible numbering considering we’re employing a lot of people, and we’re doing stuff with the land, we’re producing.”

Even farmers who are running out of groundwater may not need to sell off their land in order to restore their aquifers. Don Cameron, who grows grapes in the eastern valley near the Kings River, has pioneered a technique that involves the intentional flooding of yield fields to recharge groundwater. Older this year, when a torrent of melting snow came roaring withal the Kings, he used a series of pumps to pull it off the river and onto his vineyards. The water sank into the ground, where it refilled Cameron’s underground water bank, and the grapes survived just fine.

This kind of recharge project allows farmers to alimony their land, so it’s much increasingly palatable to big agricultural interests. The California Sublet Bureau supports taking agricultural land out of legation only as a last resort, but it has thrown its weight overdue recharge projects like Cameron’s, since they indulge farmers to alimony farming. The state government has moreover been trying to subsidize this kind of water capture, and other farmers have bought in: According to a state estimate, valley landowners may have unprotected and stored scrutinizingly 4 million acre-feet of water this year.

“I’m familiar with Dos Rios, and I think it has a very good purpose when you’re trying to provide benefits to the river, but ours is increasingly farm-centric,” said Cameron.

But Joshua Viers, a watershed scientist at the University of California, Merced, says these on-farm recharge projects may cannibalize demand for projects like Dos Rios. Not only does a project like Cameron’s not provide any inflowing tenancy or ecological benefit, but it moreover provides a much narrower goody to the aquifer, focusing water in a small square of land rather than permitting it to seep wideness a wide area.

“If you can build this string of beads lanugo the river, with all these restored floodplains, where you can slow the water lanugo and let it stay in for long periods of time, you’re getting recharge that otherwise wouldn’t happen,” he said.

As long as landowners see floodwater as a tool to support their farms rather than a gravity that needs to be respected, it will be difficult to replicate the success of Dos Rios. It’s this entrenched philosophy well-nigh the natural world, rather than financial constraints, that will be River Partners’ biggest windbreak in the coming decades. In order to create Viers’ “string of beads,” Rentner and her colleagues would have to convert farmland all wideness the state.

It’s one thing to do that in a northern zone like Sacramento, where officials designed inflowing bypasses on agricultural land a century ago. It’s quite flipside to do it farther south in the Tulare Basin, where the powerful sublet visitor J.G. Boswell has been accused of channeling floodwater toward nearby towns in an effort to save its own tomato crops. River Partners is funneling some of the new state money toward restoration projects in this area, but these are small conservation efforts, and they don’t yo-yo the landscape of the valley like Dos Rios does.

To export the Dos Rios model, River Partners will have to convince hundreds of farmers that it’s worth it to requite up some of their land for the sake of other farmers, flood-prone cities, climate resilience, and endangered species. Rentner was worldly-wise to build that consensus at Dos Rios through patience and unshut dialogue, but the path toward restoration in the rest of the state will likely be increasingly painful. California farmers will need to retire thousands of acres of productive land over the coming decades as they respond to rising financing and water restrictions, and increasingly acres will squatter the unvarying threat of flooding as storms intensify in a warming world and levees break. As landowners sell their parcels to solar companies or let fallow fields turn to dust, Rentner is hoping that she can reservation some of them as they throne for the exits.

“It’s going to be a challenge,” said Rentner. “We’re hopeful that some will think twice and say, ‘Wait, maybe we should take the time to sit lanugo with the people in the conservation polity and think well-nigh our legacy, think well-nigh what we’re leaving overdue when we make this transaction.’ And maybe it’s not as simple as just the highest bidder.”